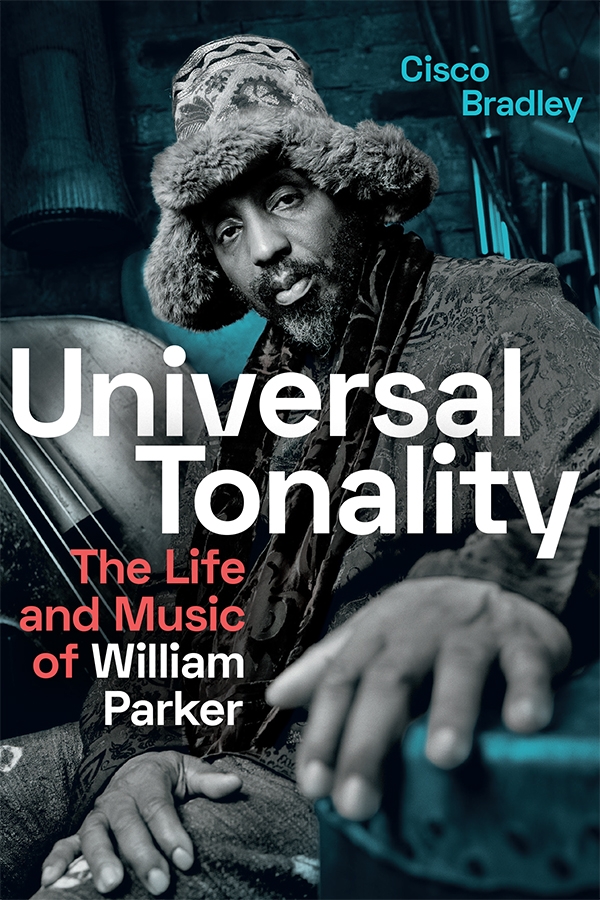

Universal Tonality: The Life and Music of William Parker

“Feelings come first; feelings, then sounds, then words” says William Parker, in regards to music and life.

On February 24th, Professor Fred Moten engaged in conversation with William Parker and writer Cisco Bradley, who is also an Associate Professor of History at the Pratt Institute. They gathered together to talk about Bradley’s newest book, Universal Tonality, and how it was shaped by conversations about William Parker’s life. The book begins with a tribute to Parker’s ancestors, an invocation of the experiences passed down through generations. Soon after, we journey through Parker’s life, tagging along for the ride as we learn more about jazz, creative inspiration, and so much more.

Born in the Bronx, music has always been a large part of William Parker’s life. He remembers around six years old his father playing Duke Ellington every night and him playing “musician” with his brother. He states, “you know how you play cowboys and Indians? Me and my brother, we would take the guns that we had and we would turn them around and pretend like they were trumpets and our favorite game was jam session, so we’d always play jam session.” Shortly after, his father bought him a trumpet and his brother an alto saxophone, and from there Parker’s journey into music took off. Parker revealed that it wasn’t until he was much older that he learned it was his father’s dream that he and his brother would one day play Duke Ellington’s orchestra together.

Growing up in the South Bronx was tough but he remained focused. Although his mother did not initially want him to be a musician (because it was a tough life), she was always there with dinner ready for him when he would return home from a gig at 3 AM. Parker to this day feels lucky for the level of support he received and attributes that support for his success as a musician. Since the age of 20 he has been a sought after bassist and has performed with artists such as Ed Blackwell, Bill Dixon, Milford Graves, Patricia Nicholson and Peter Kowald. In 1995, the Village Voice called him the "the most consistently brilliant free jazz bassist of all time,” and Time Out called him one of the “50 Greatest New York Musicians of All Time.”

In addition to recording over 150 albums, he has published six books, and has taught and mentored hundreds of young musicians and artists. In 2013 Parker received the Doris Duke Performing Artist Award in recognition of his influence and impact on the creative jazz scene over the last 40 years and to Professor Fred Moten he is, “one of the most important artists now living in the world.”

In 2014, Cisco Bradley approached William Parker about doing an interview for his website Jazz Right Now (www.jazzrightnow.com). During the interview, William wanted to talk about music as healing and Bradley felt like after the conversation they had just barely scratched the surface of Parker’s insight into music. A year later Bradley approached him again, but this time about doing a book.

Bradley says that the interviews took up approximately 35 hours of material, and yet, the conversation always continues.The best he hopes for is that Parker’s transformative music can help others access a greater consciousness in the world. Although words can never completely convey any music, both music and language are closely linked. Bradley felt it was necessary to write this book because Parker is contributing to a greater historical moment and documenting this journey was very important to him.

Music is about healing networks, Bradley says. He thinks through New York as a port city with connections to many places, being shaped by travel. What does it mean to be open to receiving in the same way as a port city?

It all starts with compassion, in the eyes of William Parker. He discusses the importance of feeling for other people as a way to conceptualize music. Deep empathy for others allows for the musician to create the music that people need in their lives. Bradley tells us how Parker was engaged with the world from a young age, remembering even the smallest details of childhood events. Bradley also mentions how Parker conveys ideas about music in their interview sessions. Parker thinks in color, demonstrating an expanded sense of music, pain, and empathy. This attunement to his surroundings allows him to access the Tone World. He speaks about all the shows that he performed from 1972-1978, and the sheer amount of experience that gave him. Trust the music, he says, let music go its own way. By allowing the music to permeate within, he shares space with the music, allowing for it to lead him through the piece, rather than the other way around. This makes way for the tone world, the ability to allow for this all-encompassing spiritual moment to take place.

William Parker and Cisco Bradley form a powerful duo, teaching us about how to be true to oneself, how to treat others with compassion, and how to include music in your personal journey to make the world a better place. As always, Professor Fred Moten brings out the rich context in which this book was written with his insightful questions.

Story by Aarlene Vielot and Shivani Joshi